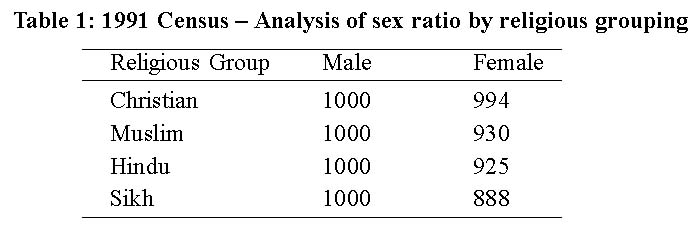

| Forum for Discussion In this issue of Samyukta, we discuss the PNDT act. In the 1991 Census, the sex ratio (i.e. number of females per thousand males) in India as a whole was 927. Further analysis of the census data showed that within this figure there were significant variations between the major religious groupings as follows: –

Concerns over the origins and implications of these figures led to a number of initiatives at the national level, leading to proposed and actual legislation. In the former category, a draft ‘National Population Policy’ was prepared and circulated for consideration, as an extension to the ‘National Health Policy (1983), which emphasised the need for ‘securing the small family norm, through voluntary efforts, and moving towards the goal of population stabilisation.’ This draft remains under consideration. In addition, the Constitution (Seventy-Ninth) Amendment Bill of 1992 contemplated that a person would be disqualified from being a ‘Member of either House of the Legislature of a State, if he was to have more than two children.’ This proposed move also awaits implementation. One key piece of legislation which did appear on the statute books between the 1991 Census and its equivalent a decade later was the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act 1994. On the face of things, this law has had, at least in part, the impact desired by its initiators, as the 2001 Census indicated a 0.5% improvement in the nation’s sex ratio, to 933 females per 1000 males. This, notwithstanding a 30% increase in legal abortions between 1991 (581,000) and 2001 (723,000), suggests that there may have been a slight diminution in the usage of pre-natal diagnostic selection. The key provisions of this piece of legislation, for which a titular amendment to the ‘Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection Act)’ is under consideration, are as follows. The Act provides for control of the operation of pre-natal diagnostic techniques for the purpose of ascertaining genetic or metabolic disorders, chromosomal abnormalities, certain congenital malformations, or sex-linked disorders. It also seeks to control the misuse of such techniques for the purposes of pre-natal sex determination, which could result in female foeticide as a result of cultural or related pressures. Such a termination of pregnancy would then be dealt with under one of the medical grounds allowed under the provisions of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act (1971). Pre-natal diagnostic procedures as defined in the 1994 Act include: – ‘All gynaecological or obstetrical or medical procedures such as ultrasonography, foetoscopy, taking or removing of samples of amniotic fluids, chorionic villi, blood or tissues of a pregnant woman for being sent to a Genetic Laboratory or Genetic Clinic for pre-natal diagnostic test’. The Act goes on to define a pre-natal diagnostic test (PNDT) as including procedures incorporating ‘ultrasonography or any test or analysis of amniotic fluid, chorionic villi, blood or any tissue of a pregnant woman conducted to detect genetic or metabolic disorders, or chromosomal abnormalities, or haemaglobinopathesis, or sex-linked diseases’. Controls also require the registration of any Genetic Centre, Laboratory or Clinic for the purposes of conducting, associating with, or assisting in the conduct of procedures linked to PNDT. Professionals involved are required to be qualified specifically to conduct PNDT, and be registered as required under the Indian Medical Council Act 1956. They may subject a pregnant woman to such techniques only in situations where: • She is over 35 years of age; • She has undergone two or more spontaneous abortions or foetal loss; • She has been exposed to potentially teratogenic agents such as drugs, radiation infection, or hazardous chemicals; • She has a family history of mental retardation or physical deformities such as spasticity, or any other genetic disease. Further, even if any of the above apply, a PNDT can only be applied if the qualified medical practitioner detects any of the prescribed abnormal conditions. The procedure also requires that details of the procedure, including its potential side-effects, should be explained in full to the pregnant woman concerned, and her written consent obtained to its being carried out. The Act specifically prohibits the use of the procedures solely for the purpose of determining the sex of the foetus, and provides for monitoring and enforcement to be carried-out by a Central Supervisory Board, Appropriate Authorities, and Advisory Committees. The punitive potential of the Act is seen in the penalties it provides, including the requirement that any breaches are triable before a Judicial Magistrate of the First Class, and that they are cognisable, non-bailable, and non-compoundable. Punitive sanctions also apply in relation to the advertisement or other forms of representation of facilities for the pre-natal determination of sex at any place, and these take the form of imprisonment for up to 3 years, and a maximum fine of Rs. 10,000/-. Any breach of the prohibitory provisions by a medical geneticist, gynaecologist, registered medical practitioner, or the owner or employee of a Genetic Counselling Centre, Laboratory or Clinic would be similarly punished. Should either breach be repeated the maximum punishments increase to 5 years and 1 lakh rupees respectively. Similar sanctions also operate in relation to a husband or relative who abets or compels a woman to undergo PNDT for the purpose of sex-identification, and this is explicitly provided for in the form of a presumption that ‘unless the contrary is proven, it shall be presumed that the pregnant woman was so-compelled’. The legislation as it stands appears to be robust and comprehensive and, as previously noted, has operated in a period when the nation’s sex ratio has adjusted marginally back towards equality. However, commentators remain less than impressed. The most striking counter against the Act being an effective piece of legislation is the number of prosecutions brought since its implementation – nil. Moreover, commentators such as MrinalPande have noted that despite the legal controls prohibiting determination tests, unauthorised clinics have been operating successfully. This was acknowledged by the Supreme Court of India which ruled that it was necessary to ban the sale of ultrasound machines to unregistered clinics, and called on the State Governments to monitor and control such bans, and prosecute those who engage in illegal sex determination. Ramachandran notes that the word ‘ultrasound’ operates to advertise a thriving business in India. He says that ‘in India, advertisements for ultrasound carry a hidden message; doctors will use the tool to reveal the sex of the unborn, opening the way to abort “negative results”, meaning in effect “females” ’. He notes that ever since the law on PNDT became operative, even the faintest hint as to the sex of a foetus would lay the doctor open to prosecution. However, ‘the law looks better on paper than in practice’, as admitted by S C Srivastava, Policy Director of the Central Government Health Ministry. Ramachandran also identifies the lack of prosecution in this area, and attributes this to the fact that abortion up to the 20th week of pregnancy is legal under the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971, even though sex selection is not. On this basis, proving that an abortion is due to sex selection, and not made on the allowable grounds under the Medical Termination Act is not an easy task. Dr Mira Shiva of the Voluntary Health Association of India (New Delhi) notes that the whole basis of such concern rests in the cultural attitudes towards, and the expectations of, women. She argues that parts of society see daughters as an expense, especially where the ‘dowry’ system operates, and amidst such customs and practices, any laws barring sex selection are unlikely to succeed. However, the perpetuation of the practice of sex selection would ‘buttress the pathological attitudes of our society which discriminates against and denigrates women.’ Conclusion REFERENCES Statutes |

Newsletter Updates

Enter your email address below to subscribe to our newsletter